Consortium begins arduous effort to honor inhabitants of UMMC's unmarked graves

Published on Tuesday, May 1, 2018

By: Gary Pettus

Jannie White of Southfield, Michigan, knows this about Speedy Ann Williams: She wore her long, black hair down to her hips and was born near Copiah County.

White also knows that her great-grandmother died at age 78 on Oct. 19, 1922 of “arteriosclerosis/insanity,” as recorded by the institution where, after a stay of two months and 16 days, she took her last breath: the Mississippi State Insane Hospital in Jackson.

White knows little else about the life and death of her Mississippi ancestor, but of the many unanswered questions she entertains about her, this is one of the most important: “Where is she?”

“To know that she was buried in a particular location would bring some closure to me and my family,” said White, who lives some 950 miles from Speedy Williams’ conceivable resting place: in one of thousands of unmarked graves on the campus of the University of Mississippi Medical Center.

For now, it may not be possible to find the exact burial sites of Speedy Williams and the other residents who died and were interred at an institution that was shuttered and relocated more than 80 years ago. With pending action in the Mississippi State Legislature, an effort to remember their lives may be gaining ground.

That effort is one of the tasks of the Asylum Hill Research Consortium, a band of experts and scholars brought together by Dr. Ralph Didlake, UMMC vice chancellor for academic affairs and director of the Center for Bioethics and Medical Humanities.

Another aim is to relocate, collect and organize the remains found in the graves. This must be done respectfully and ethically, Didlake said.

“There are more than 10,000 documented deaths at the asylum,” he said, “but we don’t know how many of those patients were buried on site.”

More than 4,300 hospital death certificates are available online through the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Some of the information Jannie White has learned about her great-grandmother is in that database, which covers the period of November 1912 through March 9, 1935 – the year the asylum closed.

NOTHING ELSE LIKE IT

By this summer, a website for descendant families should be available, said Lida Gibson, a Mississippi film documentarian who is recording the work of the Asylum Hill Project.

“People will be able to share information, including stories passed down by the families of patients, and by anyone who has memories of the asylum,” Gibson said. “There’s really nothing else like this project. It’s so important to honor these lives.”

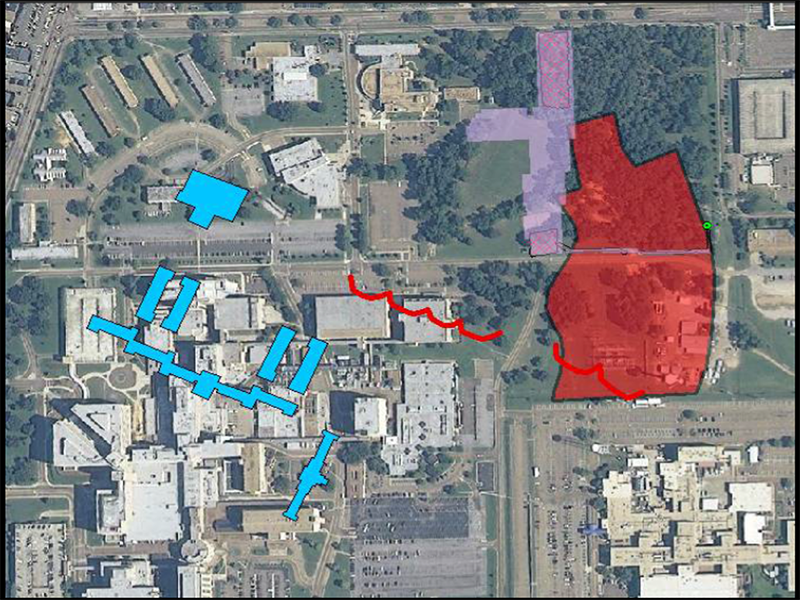

So far, 67 of those lives continue to be examined in death: That’s the number of asylum residents whose pine coffins were exposed accidentally – all but one by a road construction crew in 2013 on the northeast part of the UMMC campus.

Later, a geophysical survey showed that many more coffins lie underground across some 20 acres of UMMC, which opened in 1955.

Didlake said archaeologists are “confident” there are at least 3,000 bodies, but as many as 7,000, on campus. Last month, state lawmakers passed a bill – signed by the governor – to expand UMMC’s authority to move them elsewhere on Medical Center property.

Among the Asylum Hill Consortium’s goals is a plan to place the remains in UMMC’s Farmer’s Market facility, which offers archival conditions and 9,000 square feet of space. This will be, in effect, the new resting place of several thousand people until a permanent memorial is built.

“We don’t know if we’ll exhume everyone,” Didlake said. Construction may have obscured some of the gravesites. “But we will exhume as many as possible.”

The cost of archiving and storing the remains, creating work space for scholars and reclaiming the current burial sites for future land development is about $2.2 million, Didlake said. That’s money that won’t be requested until next year.

“This year we just wanted legislators to adjust the law,” Didlake said.

Another $3 million or so will be sought for the second part of the consortium’s plan, but the idea is to pay for it with “external funding,” Didlake said. It calls for creating a memorial to the asylum residents and a field school with a long-term scientific and educational program. All this may take another six years or more.

The asylum’s history is part of the state’s history, but because many patients’ descendants have moved from Mississippi since 1935, interest in this project extends far beyond its borders.

LIFE, DEATH AND IDENTITY

Dr. Nicholas Herrmann, a former associate professor of anthropology at Mississippi State University who now has the same title at Texas State University, has narrowed the identity of the person in the first, single grave discovered at UMMC (“Burial 1”) to 20 individuals.

This is possible because of demographic information (race, gender, age, etc.) along with isotope studies – that is, the analysis of chemical elements of a few burials. He said he may be able to narrow that number even more.

While at MSU, Herrmann directed the 2013 excavations at the Medical Center. He is preparing the technical report on the 60-plus burials.

“Will we ever be able to say certain remains are this specific individual’s? I’m not sure,” he said.

One thing that is certain about the vast majority of the people who died and were ultimately buried at the asylum between 1912 and 1935: According to records from the asylum, they were “black.”

IT’S PERSONAL

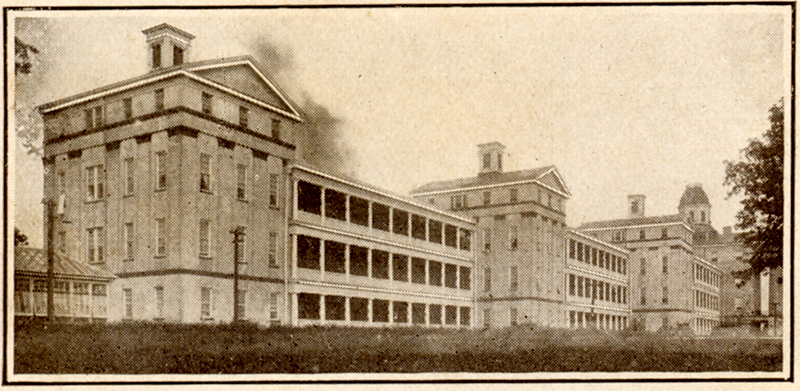

Originally known as the Mississippi State Lunatic Asylum, the facility was moved and renamed: It’s now the Mississippi State Hospital in Whitfield.

The original asylum operated from January 1855 to March 1935, but bones and skeletal fragments uncovered in 2013 are from patients buried in the 1920s and 1930s, dendrochronology studies show. Some grave markers were found, but not in their original positions, Herrmann said. These were placed in the UMMC Cemetery.

Without DNA analysis and descendants providing DNA samples, it’s impossible to match certain remains to a death record, said Dr. Shamsi Berry, assistant professor of health informatics and information management in the School of Health Related Professions at UMMC.

“And the cost would be too great,” she said.

In other ways, though, what can be learned from this project is priceless, especially to descendants like Jannie White. Particularly for those whose ancestors may have been slaves, getting a handle on personal genealogies can be a struggle. But White is determined.

“First of all, I’m a person of color,” she said. “For someone to tell me that I’m straight from a cotton field without a history, I don’t accept that.

“Before I leave this world, I want to tell my children, ‘This is who you are and this is where you came from.’”

Asylum Hill Research Consortium member institutions

The University of Mississippi Medical Center

The University of Mississippi

Mississippi State University

Jackson State University

Millsaps College

The University of Southern Mississippi

Texas State University

The University of Idaho